The Last Unicorn, The Chronicles of Narnia and the Tolkien oeuvre are, for many, definitive fantasy texts. It would be easy to conclude that they’ve reached that status purely as a result of their quality, and their (related) influence on fantasy-writing. Yet the calculus of canon formation is far more complex than a simple acknowledgement of a given work’s static value. Readers tend to think of the cadre of “classic” works and authors as relatively stable, only altered by the introduction of new luminaries. Yet a casual glance at a slightly-aged “100 Best Novels”-style volume reveals a bizarre alternate world where Benjamin Disraeli is a deeply important Victorian novelist. Read Sybil or Tancred lately? I sure haven’t, and I have a real soft spot for the bigoted old coot.

Things fall apart: whole chains of authors slough away, leaving strange, patchy, half-formed impressions of literary eras. This isn’t necessarily a process of winnowing the wheat from the chaff. Good writers are sacrificed to the marketability of the Central Figure, who wins the right to be remembered and read outside specialist circles. The Central Figure gets repackaged with Modern Classics covers, replete with dignitas. But what happens to the cultural memory of that writer’s worthy compatriots?

I’m interested in authors and novels that, while once widely-read and deeply-beloved, have now slipped out of our collective memory. Some writers certainly fade away because their work hasn’t weathered well, or doesn’t appeal to the sensibilities of a given moment. But shifts in sensibility aren’t necessarily progressive. The aesthetic judgements of the seventies aren’t automatically superior to those of the sixties, etc. What didn’t do it any more for the 1980s might appeal in the 2010s. Enough people once saw something in these works that you or I might well also see something. It’s a shame that we are cheated of the chance to love these books simply because we’ve never heard of them.

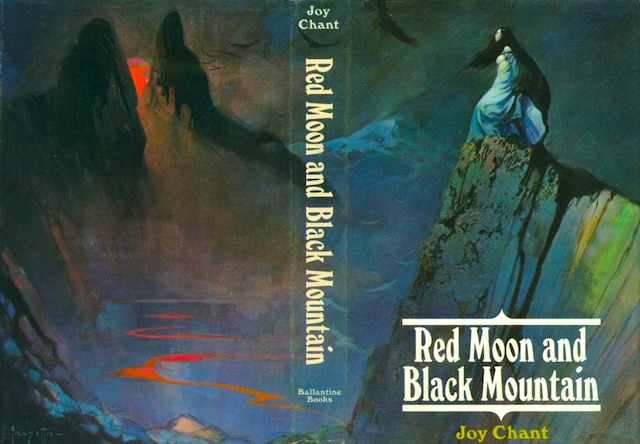

Joy Chant’s Red Moon and Black Mountain is one such forgotten “classic.” It’s an unashamed traditional epic fantasy. It comes complete with a broad cast of noble races (as familiar and somewhat cardboardy as you might expect), beautiful princesses, epic battles, talking animals, etc. There’s no shortage of Christian messages. Hell, they amount to flood-lit Christian billboards. But there’s a friendly, Unitarian Universalist sort of tone that doesn’t alienate readers who don’t share the book’s spirituality. Children (siblings Oliver, Nicholas and Penelope) fall into and save a magical parallel world: you get the idea. But as writer Teresa Edgerton, who first encountered Red Moon in the 1970s, hastens to remind us: “Any reader picking up the book for the first time might conclude after the first few chapters that he or she has seen it all before, and yet… and yet as someone who read the book when it first came out, I can vouch for the fact that none of these themes or characters seemed shop-worn and over-used back then.” It’s also one of the best executions of the genre I’ve ever read.

The prose starts strong, and stays crisp and vibrant throughout. Children on a bike-ride in the country near their home in rural England seem to demand Chant’s attention and unwavering commitment to story as much as epic battles do.

“Easter was early that year. It fell in blackthorn winter, when the blossom on the sloe could have been taken for frost, and the hawthorn had barely sprouted its buds of green and copper. Every morning the grass was patched with white, and there was iron in the air.”

Red Moon never lets go of either the directness and pull of naturalistic literary prose, or the heady intensity of mythic language. Chant’s language is ornate yet strong, like delicate jewelry made of cast iron.

Her characterization can be similarly deft. I was particularly impressed with the strong places afforded to women, particularly Princess In’serinna, Mneri and Vir’Vachal, in the narrative. All three relate to the plot in ways that could be considered primarily romantic, but that reduction wouldn’t do justice to the agency they possess.

Princess In’serinna, a powerful sorceress of an otherworldly people, must give up the magic she has sworn herself to, and which she loves, in order to regain her full capacity for human feeling and marry the rough hunter she’s come to care for. It’s a difficult decision, and she only commits to doing so should they win their battle against the forces of darkness—a battle in which she serves as a terrifyingly effective warrior.

Every sorcerer is associated with a single star. This is the source of their power, and a part of them. Her kinsman, the High King, warns her that should she relinquish her sorcery, this star will die. This sounds like a relatively straightforward (and dubious) association between sex and loss. It could even be a condemnation of marriage outside one’s aristocratic station. But the star’s death is more complex and lovely in its realization.

If they had expected anything, they had expected the star to flicker and die. But it did not. It grew. It grew as if living its million years in a moment; it blossomed like some fantastic flower of heaven. Its burning rays eclipsed its brother stars. It was the brightest thing in the sky, brilliant, vivid, lighting their awed faces with its fire. It stood above them proud, defiant, pulsing flame.

The star swelled once more then hesitated, trembling with light like a brimming glass. It hurt to look at it yet they would not look away. Then all at once a darkness appeared at its heart, and the star seemed to burst. Faster than their eyes could follow, its rim grew, spread, hurtled across the sky; and there was left only a glove of hazy, pearly light. Then that too faded. dimmed and died, and they were left, letting out their breath in a long, shuddering sigh, gazing silently at the blank place in the sky.

This otherworldly description dramatizes the unthinkable wonder of what the Princess is giving up. But it also shows her decision to follow her own path and embrace a full, messy, human life as a beautiful, moving consummation. The passionate vitality of the star’s exhaustion is, like a rich life, a short and splendid contradiction in the face of the inevitability of death.

Mneri, sister of the Princess’s husband, is a similarly determined young woman. She has both a believable, affecting romantic arc and an important spiritual and “professional” life. Vir’Vachal, the goddess she serves, is an awesome primordial earth mother. “She was coarse, and she was primitive, and she was frightening—and yet she was beautiful. She was beautiful in a way he had never dreamed of, did not understand, yet seemed to remember. And looking at her, everything that he had ever called beautiful faded, paled, seemed but husks beside her, and the very thought ‘beauty’ re-shaped in his mind until it fitted her; for it had been made of her, and for her, and now all at once it seemed a richer, brighter, more terrible thing.” Vir’Vachal’s role in the narrative’s conclusion is thrilling and unexpected. Only the book’s unusual structure, with its long denouement, makes it possible.

While the mandatory Epic Battle is present and correct (and so About God it makes The Last Battle look comparatively discreet), Red Moon’s denouement stretches on at unexpected length, and has its own tensions to resolve. The denouement isn’t really a victory lap or a tying up of loose ends so much as the result of the novel’s commitment to psychological and metaphysical follow-through. Protagonist Oliver’s participation in the Epic Battle, and the hate and violence that participation engenders or requires, have consequences. Oliver suffers a deep post-traumatic alienation from himself, his adopted people, and the spiritual fabric of his world. Oliver’s lost innocence is treated with respect, but his path to recovery does not lie in the ultimately inadequate, impossible abnegation of what he has experienced. Oliver will never again be the boy he was, but that maturity is neither fully positive, nor fully negative. “And have men sunk so far, that the best they can hope for is innocence? Do they no longer strive for virtue? For virtue lies not in ignorance of evil, but in resistance to it.” Chant’s atypical story arc doesn’t just open up different narrative possibilities, it mandates an engagement with consequences. People don’t just fall in love, they get married and then make compromises. They don’t just have to defeat the Great Evil, they have to return to daily life afterwards. This lingering bears gentler, stranger revelations than the familiar conventions of sword-and-sorcery can easily convey.

Speaking of conventions: a lot of epic fantasy exists in a purely white faux-Europe, but Red Moon’s (admittedly secondary) Humarash people are explicitly black, “dark with the garnered gold of a million summers.” This description may seem exoticizing, but everyone and everything in the book is rendered pretty equally emotively. Many of the High King’s subjects have been reluctant to answer his summons to fight the great foe. The Humarash are not his subjects, and are not obligated to risk their lives. Theirs is only a tiny country, and it is far from danger. Yet they have walked three-thousand miles to support the side of right without even having been asked to do so. It remains a powerfully affecting literary example of altruistic self-sacrifice.

Red Moon was published in 1970, the year UK Conservatives garnered a surprise electoral victory. Afro-Caribbean immigration was perhaps the big political issue of the day. MP Enoch Powell’s 1968 “Rivers of Blood” tirade against black “dependents” was not only deemed publicly acceptable, it was also considered a decisive contributory factor in the Conservatives’ 1970 win. Chant’s presentation of the Other was relatively unique in epic fantasy. It’s still relatively unique to this day, though thankfully less so. In 1970 this portrayal of black newcomers as dignified equals, and positive contributors to the civil project, must have shown an especially poignant picture of inter-racial collaboration. Given the current backlash against “multiculturalism” in Britain, even among the Labour leadership, I’m not certain Chant’s work has lost much timeliness.

As you may well have observed, and as Chant’s critics were quick to point out, this sounds like Lewis, or Tolkien. But that’s somewhat like Mark Gatiss’s moaning on Twitter about Elementary ripping him off, when Sherlock, his program, is itself obviously a descendant of Conan Doyle’s work and its many past adaptations. That includes recent popular successes such as House, and the Guy Ritchie Holmes series. George MacDonald, author of works such as The Light Princess and The Princess and the Goblin, deeply influenced a whole school of English fantasy, not just C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien. If Chant’s writing resembles that of Tolkien and Lewis, it could be because she shares a relatively similar network of influences and cultural moment.

And what if we were to agree, though there are arguments for and against this premise, that Red Moon does heavily crib from the work of these men? Lots of novels have followed and been influenced by classics in their genre. Surely while we award some points for originality, we award some for putting one’s influences to good use? Designating a movement’s Leaders and Followers, and prioritizing the contribution of the former at the expense of the latter, makes titular acts of innovation more important than strong prose, or better than particularly thoughtful work within a genre someone else “founded.” This simply isn’t true. If it were, we’d all be reading exclusively H. G. Wells forever. And frankly, who wants to? It’s important to admit that innovation is just one literary merit among many. These metaphors of literary fatherhood, and the discrediting of “imitative” creations, will sound very familiar to readers of Gilbert and Gubar’s The Mad Woman in the Attic and feminist criticism generally. Credit-allocation may be interesting for production-history junkies, but it doesn’t need to dominate what gets reprinted and talked about. It shouldn’t circumscribe the reading of those drawn to good books for their own sake.

Red Moon won the Mythopoeic award upon its publication and stayed in print for over a decade, but I believe the verdict of guides such as “Wilson & Alroy on High Fantasy Novels” demonstrates the attitude that eventually doomed the novel to obscurity:

Joy Chant, Red Moon And Black Mountain (1971)

The most slavish Tolkien ripoff I’ve yet seen, right down to the specifics: the hobbits (the three English children magically transported to the world called Vandarei) including Frodo (the messianic oldest brother Oliver), Sauron (Fendarl), the Rohirrim (the Khentors), the Numenoreans (the Harani), even Tom Bombadil (the Borderer) and Gwaihir the Windlord (the eagle King Merekarl). Sure, there are no dwarves or elves or interesting monsters, and Chant makes a major strategic error by not introducing a Shakespearean character like Gollum—everyone’s basically all good or all bad. There are also some strange ideas like Oliver’s implausibly rapid transformation into a grownup warrior who inexplicably forgets his origins. But I’ll settle for it; I’m way too addicted to Tolkien not to get a rise out of such a thing. And at least the female characters like the little girl Penny, the motherly Princess In’serinna, and the romantically frustrated teenager Mneri are much more strongly developed—actually, it’s well-written in general, although it veers into melodrama and silliness, and isn’t able to create a world as rich and believable as Middle Earth. Recommended if your copy of the Trilogy is falling apart from too many readings. (JA)

This reduction of Chant’s project into a paint-by-numbers inadequate reflection of The Master, and complete inability to cope with Tolkien and Chant’s shared genealogy, or the aspect of Chant’s writing that surpass Tolkien’s—her prose style, psychological leanings and, arguably, light touch with exposition—does a huge disservice to both authors and works. Chant becomes a sad parrot; “Tolkien” becomes a mere mechanism: disassociated from context, his work has become a litany rather than a literature, comprised of set stock elements and deviated from at everyone’s peril.

There are reasons to dislike Red Moon. It’s not simply cheesy, it’s the family-size fondue pot of epic fantasy, despite its gestures at a sort of psychological realism. Some people, understandably, are cheese-intolerant, and throw up all over the place once their cheese-threshold is passed. The writing is great, but if sentences like the following drive you nuts, the book might not be for you: “‘How will you like Kuniuk Rathen, then, Kunil-Bannoth?’ he asked; for Hairon had been charged with the hereditary wardship of Kuniuk Bannoth and the lands thereof, and was now Kunil-Bannoth—which charge and title were borne by his heirs for generations, until Garon II made an end of their house.” But then again, if you got through Tom Bombadil’s many songs, you can survive anything.

But those caveats aside, Red Moon is frankly fantastic. Women, young readers, and fans of the subgenre and/or the aforementioned similar authors might particularly enjoy it. While out of print, the book is available very cheaply online (and if anyone has any sense they’ll reprint this and books like it to tie in with the probable popularity of the Hobbit films and general rising interest in the epic fantasy genre). It’s a lush, delicious book, and I’m very grateful that my grandmother remembered it had ever existed, and passed her copy along to me.

Erin Horáková is a southern American writer. She lives in London with her partner, and is working towards her PhD in Comparative Literature at Queen Mary. Erin blogs, cooks, and is active in fandom.

Terrific review, and I’ll seek the book out.

I love aged “Best of…” lists, mostly because I do love folks like Disraeli and Robert Chambers. That seems like a completely acceptable alternate reality to me.

Very nice reminder of a book I encountered in the late seventies right after devouring Tolkien for the first time. Sadly it is one of those books that have vanished off of my shelf in the succeeding four decades. When I prowl the used book shops it is one of those I look for still.

There is so much good fantasy dismissed as derivative of JRRT. Terry Brooks Sword of Shannara is one that is IMO rightly placed in that column, but Mr. Brooks went and learned his craft and the Shannara books that followed were inventive and a pleasure to read. Stephen Donaldson is another who, both at the time and still to some extent is unfairly compared to the Good Professor T.

@@@@@Jared_Shurin Thanks! And I’d agree, the darker corners of 19th century lit are really interesting. I’d like to see Vivian Grey taught with The Picture of Dorian Gray sometime, I think it could be provocative.

@@@@@arixan Mm, it’s interesting that ‘Tolkienesque’ is used so often as, if not an outright slur, often a slight dismissal of the book’s sucess in that vein and its potential innovations in that mode.

@ErinHoráková It probably stems from some party where a Harlan Ellison style character was dismissive of JRRT. I remember a lot of that in the Eighties and Nineties before the films were released.

It is easy to dismiss Tolkien because his work is the primary foundation of younger fantasy writers build on, purposefully or otherwise. I’d like to see someone do a James Branch Cabell read/reread or a look at some of the other fantasy that was being published concurrently with LotR.

I read it and enjoyed it myself. While I’ve lost my copy in one of my moves, for some time after reading it, I kept looking for more books by Joy Chant.

@@@@@ 5. arixan That’s really interesting, I’d never heard of James Branch Cabell! Will have to check him out!

@@@@@ DrakBibliophile –it’d be interesting to hear from someone who’s been able to lay hands on the sequels, I’m curious about them. I hear they’re not as good, but then, that’s from the same people who didn’t really seem to get RM&BM.

There were more books by Joy Chant — The Grey Mane of Morning (1977) and When Voiha Wakes (1983) — I think they were direct sequels, although my memory is a little dim as I haven’t read any of them in a long time. Now I think I’ll dig them out and read all three again! I totally agree that “innovation” is an overrated quality. Tolkien’s value isn’t that he was the first to take world-building to the heights, any more than Beethoven’s value was that he invented the symphony — Tolkien wasn’t the first, and Beethoven didn’t do that! They are both titans for plenty of other reasons. Anyway, your appreciation of Chant is very welcome.

If you haven’t read Grey Mane of Morning — you must! It’s is the sequel to Red Moon Black Mountain, a markedly more mature work, a fully adult novel.

Chant’s secondary world is plausibly more ‘primitive’ than say, a Tolkien’s, yet is filled with more splendor of earth-and-land magic than he ever imagined.

Love, C.

Both Red Moon… and Cabell’s works were published in the terrific Ballantine Adult Fantasy series. It would be fascinating to see someone do a reread of those!

Fabulous review. If I hadn’t just re-read my copy of RM & BM a year or so ago, I’d go get it off the shelf immediately. In fact, I might just re-read it again anyway.

@9. Tehanu: “Tolkien’s value isn’t that he was the first to take world-building to the heights, any more than Beethoven’s value was that he invented the symphony — Tolkien wasn’t the first, and Beethoven didn’t do that!”–really well-put. And if you felt like giving some pre-Tolkien or contemporary examples of deep world-building, I certainly wouldn’t be opposed! Peake comes to mind.

@@@@@ 10. Zorra: Oh that does sound exciting, will have to try and find it on Amazon now. And I think that’s a strong description of the difference between their worlds.

@11. lampwick That’s a good idea! For people reading comments, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ballantine_Adult_Fantasy_series this is the list in question.

@12. Rachel Neumeier Thanks, and it can’t hurt! Quite sad I buggered my hardcover’s dustjacket trying to reinforce it with tape when it was flaking to bits. Now I can’t look at the thing without guilt and annoyance at myself, had to shelve it somewhere inconspicuous…

The Grey Mane of Morning, that’s the one! I stumbled across it in 8th grade, never had a clue what was going on, and loved it anyway. I recall it being tremendously beautiful and evocative (with really cool horses). Never knew there were other books (perhaps it might have made a bit more sense if I’d started with the first). I shall have to start hunting used bookshops for this whole series now…

And I just found copies of both RED MOON and GREY MANE on Paperbackbookswap. Score!

Very cogent point, Ms. Horakova, about the relative value of innovation and the credit due to successors working within the innovated forms. It would surely be limiting if we stopped only at Original works and passed on those that develop and further an innovation.

Tehanu (@9): The Grey Mane of Morning and When Voiha Wakes are not direct sequels. Though they are both set in the same world of Vandarei, they are fully secondary-world fantasy with no intrusions from our (primary) world, and their events are not in any strict chronology with Red Moon and Black Mountain. Grey Mane feels more like a prequel about the Khentorei horse folk, while Voiha is more a timeless parable (the title is an aphorism that means, roughly, “When pigs fly”). Both are recommended to anyone who enjoys Red Moon.

As well as Ms. Chant’s other published work, The High Kings, a retelling of Celtic history and legends found in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s The History of the Kings of Britain (such as the story of Llyr and his daughters) as tales recounted ’round the fire to King Arthur (who becomes his own legend in the book’s last tale). The original illustrations by George Sharp are worth the price of the book by themselves, as well.

Oh, this is a book I haven’t thought of in years. When I was an impressionable 16 year old in the mid-80s, I was doing after school babysitting for an avid fantasy reader. She introduced me to many, many books and authors, including RM&BM. She’s a large part of why I’m the reader I am today. (Sadly, it also means I don’t own a copy as I read hers.) Thank you for the reminder of a lovely book and an important part of my life I don’t think of often these days.I suspect a big reason the book has been forgotten is that the author is a woman, and addresses some of the concerns of fiction written by women. The dismissive paragraph you cite is incredible; there are so many differences between Chant’s treatment of her material and Tolkien’s that I can only wonder what book the author read.

According to Wikipedia. Chant is still alive and not that old. She could be asked about her influences.

What struck me the most about the book when I first read it is not its high fantasy elements, which are as you say derivative, though perhaps as much of Arthurian and Norse mythology as Tolkien, but the characters and the places, both of which are much different from Tolkien’s. The structuring element of a good-vs-evil conflict is, as you say, a common one, and I never thought it was especially important. But the characters are still memorable.

@@@@@ 18. Mary Beth re: Paperbackbookswap–oh, excellent tip, didn’t know this existed!

It occurs to me that, when I read Red Moon and Black Mountain, I had already read Susan Cooper and Alan Garner, but I hadn’t read any Tolkein.

I loved it, partly for the great dramatic sweep of it, and partly for the little details, like the little girl who is being kept captive with the princess, and how horrible her mouth feels because she hasn’t been able to clean her teeth for a few days!

There were images, too, that are still crystal clear in my mind, like the goddess on the pony who isn’t walking across the meadow but sinking into it and leaving a furrowed trail behind.

And I liked it because Oliver had such a difficult journey back to this world, and it made sense that his path would be harder than the younger children.

I didn’t enjoy the other books in the same universe quite so much, but the High Kings is one of the best retellings of Celtic myth I know, and the illustrations are marvellous.

Joy Chant really does deserve to be better known.

@19. Eugene R.: Thanks for this really informative and helpful gloss on Chant’s other work!

@23 ErinHoráková: I discovered Paperbackbookswap several months ago and it has been FANTASTIC for acquiring books that are now out of print. The SFF selection tends to be lean, but there can be real gems. I’ve swapped nearly 30 books so far!

@21. RandolphF : Chant’s said elsewhere that her secondary world was created well before Tolkien became a benchmark, but I think it’s difficult for artists to be cognizant of their influences sometimes? Woolf went on about how she’d never read any Freud (while his work was being translated in her husband’s publishing company and she was having Anna Freud over to dinner, somehow she managed to escape all knowledge of it!!), who in his turn went on about how he’d never read any Nietzsche. Both writers were afraid of being or being seen to be influenced/immitative, and the both were probably lying to themselves as much as to whoever they said this seeming-bs to. Ultimately–I don’t think Chant’s account of her influences matters that much, at least to me? It could be illuminating to trace the threads of her concerns and stylistic mannerisms back to antecedents, sure, but working to establish a geneology somehow seems to participate in the uncertain work of genre-heraldry.

I really concur with your remarks on gender, characterization, and the particularity of Chant’s work.

@24. Lesley A –weirdly, for all the drudge of carting the damn ring back, I’m not sure Tolkien delivers the same ‘eugh, my TEETH!’ level of ‘questing is harsh in a way that’s physically palpable’. Though I could be failing to remember some instances, it’s been a while since I read that series.

There were images, too, that are still crystal clear in my mind, like the goddess on the pony who isn’t walking across the meadow but sinking into it and leaving a furrowed trail behind.–oh god I LOVE that image, it’s searingly powerful.

@26. Mary Beth I just wish there were better UK equivalents! BookMooch could use, well, more *books* to choose from, and Read It Swap It’s ‘no actually swap directly with one person’ thing is vexing, because whoever’s going to want the Bad Gift Torchwood Novel probably /isn’t/ trying to off-load the Laplanche I need for my thesis, strangely enough. I’m hoping that if one waits patiently, gems will crop up (and at least someone finally wants Review Books What I Disliked…).

@29. ErinHoráková: Ah, yes. Somehow I picked up on the “southern American writer” and missed the “living in London” bit. (At which, profound envy!) At least there’s always used bookstores, though one really has to go just for the visceral pleasure of browsing rather than for the hope of finding exactly what one is looking for.

I’ve noticed that PBBS suffers from the “needing more books” issue quite a bit, though. You CAN find good things, if you’re patient, but there are sure a lot more bodice-rippers than there are SFF. Not that I’m averse to a good romance novel (though I prefer the variety with enthusiastic consent) but for some reason people tend to hold on to the Really Good Stuff rather than listing it for swapping!

When I was studying librarianship, the head of department had taught Joy Chant, back when he was living in Wales, and she told him that she hadn’t read Tolkien when she wrote the book. Obviously a lot of people even then recognised the elements, and yes, C.S Lewis is there too; perhaps there are simply influences in common.

I agree this is a classic that hasn’t exactly been forgotten, but hasn’t had the recognition it deserves. It’s not that long, either, just a standard-length children ‘s book which I found in Puffin for 80 cents! And then they did the Ballantine edition, with an adult cover and a higher price.

it had its own fandom, way back when; I once went to a con masquerade as Princess In’serinna, in a green and silver dress. And people had heard of it.

@@@@@ 31. Wolfborn: “I once went to a con masquerade as Princess In’serinna, in a green and silver dress. And people had heard of it.”

Oh wow, interesting, I wouldn’t have thought people cosplayed that!

I’m so glad there are people who love these works. I am smug, tho: I have carried around my paperback copies of her Gray Morning and Red Moon for years, and also, I have a hard copy of The High Kings. (The trouble with paperbacks is that the paper just doesn’t old up to Time (ie, the acid issue)). They are excellent! And well written! Not in the high English Tolkien used (I have read and loved the LOTR several times, by the way). It never occurred to me that Chant’s books should be compared in any way to Tolkien; the worlds they have invented are quite different, but excellent in their own way. I am so disappointed that she has not written anything else. However, I understand she is working at gardening and family, so I will forgive her!

As to Narnia: CSLewis’ books have no depth, the characters are silly if they are not overtly ‘heroic’, and are much too didactic for my taste.

Hi Erin – Thanks for this remembrance of Joy Chant’s Red Moon and Black Mountain. I read this in the early 1970s and then again in the mid 2000s — and I loved the story both times. I didn’t find it “cheesy”. At the time it came out, everyone and their grandmother seemed to be trying to jump on the heroic fantasy bandwagon, yet Chant’s voice always struck me as incredibly authentic – and still does. For readers interested in her books, The Grey Mane of Morning and When Voiha Wakes aren’t direct sequels per se to Red Moon and Black Mountain. What ties them together, other than fine writing and wonderful plots, is that they all take place in the land of Vanderai. They are really three stand-alone books that all take place in the same world, but in quite different eras. All are worth seeking out.

P.S. While we are on the subject of Forgotten Fantasy Classics, check out Roderick MacLeish’s fine novel, Prince Ombra – now back in print.

Some of us appreciate the Christian theology that underlines Red Moon Black Mountain and the 27th chapter that begins with the face-off between Lucifer and the archangel Michael is truly one of the best in modern fiction. I wish there were more of the same from Ms. Chant. A shame this didn’t get made into a movie.

I read this many years ago, borrowed from the local library, and the image that stayed with me for a very long time was the depiction of the Lucifer figure, not as monstrous in the way of Tolkien’s figures of evil, but as heart-stoppingly, seductively beautiful, in a way that the protagonist did not expect and found hard to resist. As someone who was blown away by Tolkien, and who disliked many of the poor imitations that followed, it never even occurred to me that Chant’s world could be considered Tolkien-lite. The differences in the world building outweigh the common themes, none of which are original to either writer. I agree it has a lot of thematic similarities to Lewis, but Chant is a far better writer for my money.